Linguistic evidence for a major population change in Central California is supported by archaeological evidence. Over the past 25 years, excavations have revealed more details about the specifics of the transition as Penutian-speaking peoples moved into the Monterey Bay, pushing back or absorbing the much smaller group of Hokan-speakers in their path over an extended period of time. Further, the much more meager data from Esselen territory suggests that the Esselen were an intact population until Spanish contact rearranged their lives.

Linguistic data and theories have long been used to as a tool to supplement archaeological research. In Central California, for example, various population movements were suggested almost as soon as the linguistic patterns were identified (cf. Dixon and Kroeber 1913, 1919; Sapir 1917).

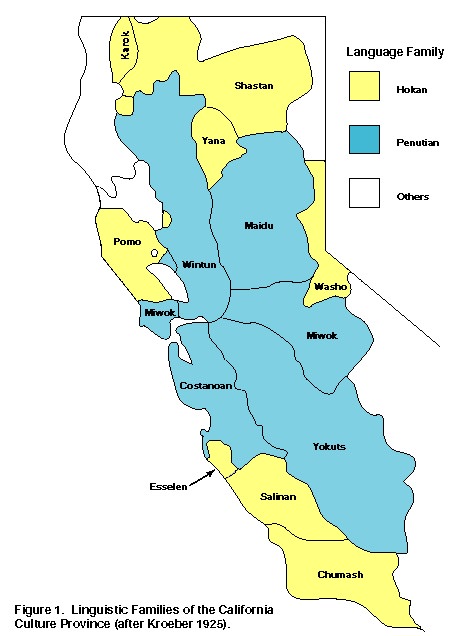

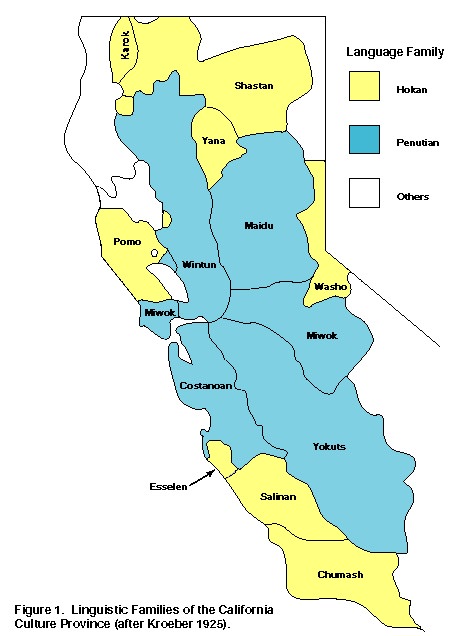

One of the first detailed maps of Central California linguistic groups (see Figure 1) was published by Kroeber in his Handbook (1925).1 Based on the linguistic patterns, researchers immediately postulated that the Hokans had once been contiguous, occupying most of California, and that a subsequent intrusion by Penutian groups had created the widely separated pattern which was appearing.

Since that date, the idea of a Penutian intrusion has been discussed almost continuously in the literature (cf. Kroeber 1923, 1935; Klimek 1935; Baumhoff 1957; Taylor 1961; Baumhoff and Olmsted 1963, 1964; Hopkins 1965; Gerow 1968, 1974; Breschini 1976, 1980, 1981, 1983; Krantz 1977; Elsasser 1978; Levy 1978, 1997;2 Breschini and Haversat 1981, 1982a, 1985), Moratto 1984; Lathrap and Troike 1988; Shaul 1988).

A major investigation into the question, summarizing research begun in 1972, was presented by Breschini (1983). Moratto, in his massive work on California archaeology (1984) presented a model identical in most respects to Breschini's, but which had been formulated independently beginning in approximately 1967 (Moratto, personal communication). Research along similar lines has been conducted, generally independently, by a number of other scholars in recent years, and the overall model of Penutian intrusion into Hokan territories is now widely accepted.

Applying the overall picture, as painted by researchers since 1913, to the Monterey Bay area we can extrapolate the following areas of general agreement:

1) The territory occupied by the Esselen at the time of historic contact was pretty much always Esselen territory.

2) The area to the north of the Esselen, occupied by Rumsen and other Costanoan/Ohlone groups, speakers of Penutian tongues, was once occupied by speakers of Hokan tongues, possibly the ancestors of the Esselen. At some time in the past, a change from Hokan to Penutian occurred throughout this area. The change was more gradual than rapid, and involved some degree of population replacement.

The primary area of disagreement is in the time of the change. Some researchers favor ca. A.D. 500-1000, while others suggest about 500 B.C. These ideas are explored in the following sections.

Esselen Territory at Historic Contact

The Esselen was one of the least numerous groups in California, and is often cited as the first California Indian group to become culturally extinct. Some place cultural extinction as early as the 1840s (Kroeber 1925:544; Hester 1978:497; Beeler 1978:3). Reasons cited generally include the small size of the group, and close proximity of Esselen territory to two of the three earliest California Missions.

When the Spanish colonized the Monterey area, the Esselen resided in the rugged Santa Lucia Mountains. Much of their territory is now included within the Ventana Wilderness Area of the Los Padres National Forest. Recent research has adjusted the northern and eastern boundaries from those depicted in Kroeber (1925). Our best estimate of this territory is shown in Figure 2 (see Breschini et al. 1983 and Breschini and Haversat 1994 for a discussion of Esselen boundaries). Early estimates placed Esselen territory at or below 650 square miles (Cook 1974a), but recent research shows that the Esselen controlled an area closer to 850 square miles.

The Sargentaruc area around the lower Big Sur River was traditionally included within Esselen territory, occasionally as a bicultural/bilingual area. Milliken (1991), using data from mission records, now places this area within Rumsen (Costanoan/Ohlone) territory. There is some evidence that a few Rumsen moved south into this area just after Spanish contact. These individuals may have been subsequently baptized as residents of "Sargentaruc," leading to some confusion over the cultural affiliation of that district. Archaeological excavations in the Big Sur area have not found prehistoric deposits whose characteristics match those of Rumsen territory. [See The Sarhentaruc Problem, by Gary S. Breschini, Trudy Haversat and Tom "Little Bear" Nason.]

The "last" Esselen were baptized in 1808. However, recent evidence suggests that some Esselen were able to retreat into the rugged interior (the upper Carmel River, Pine Valley, Tassajara Creek, etc.), where they appear to have survived at least into the 1840s (Breschini and Haversat 1993, 1994, 1995a; Edwards et al. 1997). [See also Post-Contact Esselen Occupation of the Santa Lucia Mountains, by Gary S. Breschini and Trudy Haversat.]

Figure 2. Esselen Territory and Boundaries.

[[For a larger, pdf version (436 k) click here (it will open in a new window)]

The time depth of the Esselen within their ethnographic territory can be estimated based on archaeological research, particularly radiocarbon dating. Early radiocarbon dates are listed in Table 1. Not shown in this table are two sites (CA-MNT-1228 and CA-MNT-1232/H) on the southern border of Esselen territory in the Big Creek drainage. Radiocarbon dates from these sites range between 4530-5260 and 3600-5830 B.P., respectively (Jones 1995).

It is clear from these early dates that Esselen territory was largely occupied by about 4500 B.P., if not earlier. As shown by Table 1, most of these sites are dated by only a single date, so there is a distinct possibility that earlier dates will be forthcoming. Finally, based on current evidence, there is no reason to believe that these inhabitants were anyone other than the Esselen and their immediate ancestors.

Table 1. Early Radiocarbon Dates from Esselen Territory

(uncalibrated; from Breschini et al. 1996).

| Site | Location | Date/Range | Reference |

| CA-MNT-44 | Tassajara Creek | 3390 ± | 95 | Breschini 1973a |

| CA-MNT-73 | Big Sur River mouth | 4120 ± | 100 | Jones 1995 |

| | 4140 ± | 110 |

| | 4170 ± | 100 |

| | 4260 ± | 80 |

| | 4350 ± | 60 |

| | 4440 ± | 80 |

| | 4490 ± | 90 |

| CA-MNT-88 | Big Sur River drainage | 3190 ± | 100 |

| | 3610 ± | 105 |

| CA-MNT-254 | South coast | 4630 ± | 110 |

| CA-MNT-478 | South coast | 3870 ± | 95 | Jones 1995 |

| CA-MNT-838 | Reliz Canyon | 4310 ± | 225 |

Esselen Territory Prior to the Penutian Expansion,

and the Transition from Hokan to Penutian

Based on linguistic patterns alone, a number of researchers have suggested that what is now Costanoan/Ohlone territory must have been occupied at an earlier time by speakers of Hokan tongues, most likely the ancestors of the Esselen. Early researchers included Kroeber (1923) and Klimek (1935). More recent investigations include Taylor (1961), Gerow (1968), Breschini (1976, 1980, 1981, 1983), Krantz (1977), Beeler (1977, 1978), Levy (this volume), and Moratto (1984). Most of these researchers only touched on this idea, but a few dealt with it in more detail.

Levy's (1997) model will not be reiterated in detail. The Central California interactions in Krantz's model were based on discussions between Krantz and Breschini from 1975 through 1977 (Krantz was chairman of Breschini's dissertation committee), and first published in a series edited by Breschini. From these discussions, Krantz derived a model, including formal rules for population movement based largely on cultural geography, to account for linguistic patterns.

The remaining two models, by Breschini and Moratto, are remarkably similar in their formulations for the Central California coast (compare Breschini's Figure 9 with Moratto's Figure 11.6, and Breschini's Figure 11 with Moratto's Figure 11.7). The primary difference (seen in Breschini's Figure 11 and Moratto's Figure 11.7) is the initial circumscription of the Santa Cruz Mountains by the expanding Penutian speakers which is postulated in Breschini's model. This was based on economic factors:

The change from Hokan to Penutian speakers . . . appears to have taken place along the Central California Coast only where a very specific combination of several specific factors was present. The necessary factors were, as far as can be identified a present, a combination of relatively level areas of oak grassland in reasonable proximity to either the ocean or the San Francisco Bay, and sizable areas of marshes [Breschini 1983:70].

While Moratto's figure 11.7 does not show a circumscription of the Santa Cruz Mountains by the expanding Penutians, his discussion (1984:557) clearly identifies the types of factors noted above. Moratto states, for example, "It is notable that the extent of the early Utian radiation seems to match the distribution of marshlands." Based on this, differences between the two maps appears to be a minor oversight, as the significant differences between the two models are negligible.3

In a significant review titled "Californian Historical Linguistics and Archaeology," Lathrap and Troike examine the problem in detail. They conclude:

Breschini, in his monograph Models of Population Movements in Central California [Prehistory] approaches these problems in precisely the way we are advocating. We find his detailed depiction of the intrusion on Penutian on Hokan, or more specifically of Costanoan (Ohlone) on Esselen, totally convincing (Breschini 1983: Fig. 11). We would refer the reader to this monograph as the definitive treatment of the Esselen problem to date [Lathrap and Troike 1988:104].

There is one clear difference, however, between Breschini and Moratto's models and Levy's model. Breschini and Moratto both place the major radiation of Penutian (or Utian) speakers between about 4,000 and 2,000 years ago. Levy places the change much more recently. For example, Levy (1979) notes:

A similar radiation into new coastal areas may have characterized the Monterey Bay Costanoan expansion of Period 2. Many terms referring to faunal and floral taxa characteristic of coastal ecosystems are patent borrowing between languages of unrelated families. . . . Terms for shark, whale, sea otter, and pelican are shared by Esselen and a number of adjacent Costanoan languages.

Thus, while all three researchers agree on the fact of the Penutian radiation, and even on many of the finer details, Levy places the Proto-Costanoan separation at 1442 B.P., and the Monterey Bay expansion in his Period 2, at about 810-892 B.P.

As Levy (1997:104) notes, two of his four periods of great linguistic change (derived from word lists and other linguistic methods) also have precise archaeological correlates. His Period 1 coincides with the generally accepted date of A.D. 1500 for the inception of Phase 2 of the Late Horizon (or Period). His Period 3 coincides with the A.D. 500 date assigned to the beginning of the Late Horizon.

Archaeological Evidence for the Transition

from Hokan to Penutian

Jones, citing Dietz and others, has consistently argued against the Hokan/Penutian Transition occurring at the Early/Middle Transition, preferring a later date. His main argument against the early transition in the Monterey Bay area relies on data from the Big Sur coast, where there is no change. While there was no change on the Big Sur coast (indeed, we have predicted that there would be no change), there was a significant change in the Monterey Bay area, and we have evidence that it occurred at the Early/Middle Transition.

To take these ideas one at a time, on the Big Sur coast, an area controlled by Hokan speakers, there is no evidence for significant change at the Early/Middle Transition. There is, however, substantial evidence for environmentally-induced change at the Middle/Late Transition. This is shown by Jones' own research:

Cultural changes marking the transition from the Early to the Middle Period [1000-600 B.C.] are generally not strong, and it is not surprising that earlier archaeologists in adjoining areas (e.g., Greenwood 1972; Rogers 1929) did not recognize a significant cultural break at this juncture [Jones 1995:213].

There is little reason to attribute patterns in the Early/Middle Period record to environmental change. . . . Trends in diet and exchange are readily explained by slow population growth, simple intensification, and increased diet breadth and diversity [Jones 1995:214].

There is, however, evidence for change on the Big Sur coast during the Middle/Late Transition, A.D. 1000-1300. Jones notes:

There is ample evidence for serious environmental problems between ca. A.D. 1000 and 1400, associated with the Medieval Warm Period. These events occurred at a time when human populations were probably very high and were approaching a significant demographic threshold [Jones 1995:216].

The abrupt transitions in the archaeological record ca. A.D. 1300 are consistent with extreme resource stress and possibly a brief, rapid decrease in human population. In the face of extreme drought, the already intensified, partially marine-focused economy could no longer provide an ample resource base [Jones 1995:219-220].

Jones concludes (1995:222), "In short, the Middle/Late Transition on the Big Sur coast and elsewhere cannot be adequately portrayed in terms of simple intensification or cultural evolution."

So we have, on the Big Sur coast, an area always controlled by Hokan speakers, no evidence for significant cultural change at the Early/Middle Transition, while substantial evidence for environmentally-induced change at the Middle/Late Transition.

Just to the north, in the Monterey Peninsula area, the picture is considerably different. The Early/Middle Transition was a time of considerable change, with most previously occupied sites being completely abandoned, and new sites being created in different areas. The subsistence patterns changed drastically as well.

The Early Period sites on the Monterey Peninsula which have been tested, and which exhibit a significant break at the end of the Early Period component, include the following: CA-MNT-17, -95, -108, -116, 148, -170, -387, and -391 (Breschini et al. 1996). These sites are residential bases located in close proximity to the coast; many subsequently served as Coastal Gathering sites (cf. Breschini and Haversat 1991) during the Late Period. These Early Period sites are generally of moderate to considerable size, but generally are not particularly deep. They appear to have been occupied repeatedly for a considerable period of time, with habitation not tightly focused to a specific locality. Typical examples of the Early Period residential bases are CA-MNT-148 and -170, both in the Pebble Beach area.

The primary characteristic of the Early Period sites is a lack of substantial resource specialization: they generally do not reflect the intensive exploitation of resources and intensive occupation which is typical of Middle Period residential bases. Most of these sites resemble each other fairly closely, with differences attributable to local environmental conditions.

New evidence, however, suggests that two of these sites (CA-MNT-108, on the Monterey Peninsula, and CA-MNT-234, in Moss Landing) were used, in part, for intensive fishing near the end of the Early Period. The primary fish exploited were small, nearshore pelagic species (topsmelt/jacksmelt; herrings/sardines), which were probably captured using dip nets from the shore (Breschini and Haversat 1995b).

After about 2,000 years of occupation, the Early Period sites were gradually abandoned between about 3,000 and 2,500 B.P.

Another series of sites had either the first occupation, or the first substantial occupation during the Middle Period. In most cases, these Middle Period cultural deposits are extremely large, relatively few in number, and exhibit different characteristics than the Early Period sites. They appear to have been occupied intensively for a limited period of time, with habitation tightly focused to a specific locality. They exhibit intensive exploitation of resources and intensive occupation, generally forming very large and often very deep deposits (the deepest, CA-MNT-12, is over six meters in depth). Radiocarbon dates on these sites are often tightly grouped, with most lying between about 1600 and 2200 B.P. (uncorrected radiocarbon dates based on shell). Typical dates for the most extensively dated Middle Period site on the Monterey Peninsula are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Radiocarbon Dates from CA-MNT-101

(uncalibrated radiocarbon dates based on shell).

| Late | Middle | Early |

| 1020 | 1600 | 3870 |

| 1690 | 3780 |

| 1820 |

| 1820 |

| 1880 |

| 1950 |

| 2100 |

In addition to the coastal adaptation, these sites are also known from the interior, particularly the Carmel Valley. There the sites exhibit different characteristics. The marine shell which makes up such a significant percent of the coastal mounds is virtually absent. Instead there is evidence of intense acorn exploitation. The only site of this type from the Carmel Valley which has been dated (CA-MNT-33a) was found to be 2285 ± 100 at the base (uncorrected radiocarbon date on shell). Analysis of the shell beads, however, suggested the site spanned most of the Middle Period (Fenenga 1988:101). The differences between this site and the coastal ones suggests CA-MNT-33a was most likely a late fall or winter village.

To summarize the evidence from the Big Sur coast and the Monterey Bay, we have a evidence for significant change at the end of the Middle Period. Some time after 1600 B.P. the large sites with their evidence of extensive exploitation and habitation disappear and a series of new sites appear, this time in widely dispersed locations and of varying types. This sudden change can probably be attributed to high populations, perhaps approaching a significant demographic threshold, and the beginning of the Medieval Warm Period. Jones found good evidence for this on the Big Sur coast, and this explanation seems to account for the disappearance of the large Middle Period villages in the Monterey Bay.

However, if these are the causes of the Middle/Late Transition changes, we need to look elsewhere for the changes associated with the Hokan/Penutian transition.

The Early/Middle transition, sometime after 3,000 B.P., seems a much more likely candidate for the Hokan/Penutian transition. Substantial changes took place in the Monterey Bay (as detailed above), but on the Big Sur coast, as Jones (1995:213) notes, "there is little reason to attribute patterns in the Early/Middle Period record to environmental change," and "trends in diet and exchange are readily explained by slow population growth, simple intensification, and increased diet breadth and diversity" (Jones 1995:214).

If there was no environmental correlation for the Early/Middle transition then a cultural one is most likely. It can be argued that Jones did not find evidence for such a cultural change at this time on the Big Sur coast, but the Big Sur area remained Hokan speaking so no such change would be expected. The lack of change on the Big Sur coast cannot speak to the issue of change in the Monterey Bay area. In fact, on the Monterey Peninsula we have significant changes in settlement and subsistence patterns which are not mirrored on the Big Sur coast. This is exactly what would be expected for the Hokan/Penutian transition as theorized by both Breschini and Moratto.

The Problem of the Missing Late Period Villages

One further point can be raised. Based on mission records, there are thought to have been five principal Late Period Rumsen villages (Achasta, Ichxenta, Tucutnut, Socorronda, and Echilat). These villages are where the vast majority of Rumsen baptized at Mission Carmel originated. However, the identification of these villages archaeologically has been a problem. There are a number of likely candidates which have been examined, but in most cases archaeological data suggests a Middle Period date (for example, CA-MNT-33a, as discussed above). No single large Late Period villages are known in the appropriate areas. The closest is a cluster of five or ten sites which together probably constituted the Late Period village of Echilat (Breschini and Haversat 1992).

The available information suggests that there may actually have been about five principal Rumsen village during the Middle Period. As noted above, most of these large Middle Period villages were abandoned during the Middle/Late Transition, possibly because of large populations and changing environmental conditions. The names of these villages probably persisted into the Late Period as district names, long after the villages were abandoned. This suggests significant cultural continuity from Middle into Late Period, and is another argument against a late Hokan/Penutian transition.

Summary

There is substantial evidence, first from linguistic theory and now from archaeology, for the Hokan/Penutian Transition in the Monterey Bay area.

The primary argument has been when the event occurred. New evidence supports the theoretical model proposed independently by both Breschini and Moratto, which includes an early (ca. 500 B.C.) date for the Hokan/Penutian Transition in the Monterey Bay area.

1 Although Kroeber's Handbook was published in 1925, most portions reportedly were completed as early as 1918.

2 Levy's 1997 paper circulated as an unpublished manuscript since 1979.

3 It is gratifying to note that recent archaeological research (Hylkema 1991) has found that the change from forager to collector in the Santa Cruz Mountains did not occur until after A.D. 1000. This supports the pattern shown in Breschini's Figure 11.

REFERENCES

Baumhoff, M.A. 1957. An Introduction to Yana Archaeology. Reports of the University of California Archaeological Survey 40.

Baumhoff, M.A. and D.L. Olmsted. 1963. Palaihnihan: Radiocarbon Support for Glottochronology. American Anthropologist 65(2):278-284.

Baumhoff, M.A. and D.L. Olmsted. 1964. Notes on Palaihnihan Culture History: Glottochronology and Archaeology. University of California Publications in Linguistics 34:1-12.

Beeler, M.S. 1977 The Sources for Esselen: A Critical Review. Proceedings of the Third Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Beeler, M.S. 1978 Esselen. The Journal of California Anthropology Papers in Linguistics. Malki Museum, Banning.

Breschini, G.S. 1972. Archaeological Investigations at MNT-436, the Kodani Site. Monterey County Archaeological Society Quarterly 1(4).

Breschini, G.S. 1973a. Excavations at MNT-44. Monterey County Archaeological Society Quarterly 2(4).

Breschini, G.S. 1973b. Rock Art in Monterey County. The Pine Cone, March 8.

Breschini, G.S. 1974. Ethnography of the Esselen. Ms. on file, Archaeological Consulting, Salinas.

Breschini, G.S. 1976. Area Indian Cultures are 9,000 Years Old. Salinas Californian, July 5.

Breschini, G.S. 1980. Esselen Prehistory. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for California Archaeology, Redding.

Breschini, G.S. 1981. Models of Central California Prehistory. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for California Archaeology, Bakersfield.

Breschini, G.S. 1983. Models of Population Movements in Central California Prehistory. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1981. Archaeological Test Excavations at CA-SCR-93. Coyote Press, Salinas.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1982a. Monterey Bay Prehistory. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for California Archaeology, Sacramento.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1982b. Osteometric Comparisons of Costanoan Skeletal Populations. Paper presented at the Costanoan Skeletal Biology Symposium, San Jose State University, San Jose.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1985. Linguistic Prehistory of South-Central California. Paper presented to the Symposium on Central California Prehistory, San Jose State University, San Jose.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1989. Archaeological Excavations at CA-MNT-108, at Fisherman's Wharf, Monterey, Monterey County, California. Coyote Press Archives of California Prehistory 29.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1991. Archaeological Investigations at Three Late Period Coastal Abalone Processing Sites on the Monterey Peninsula, Monterey County, California. Coyote Press Archives of California Prehistory 33:31-44.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1992. Baseline Archaeological Studies at Rancho San Carlos, Carmel Valley, Monterey County, California. Coyote Press Archives of California Prehistory 36. Coyote Press, Salinas.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1993. Phase II Cultural Resources Investigations for the New Los Padres Dam and Reservoir Project, Carmel Valley, Monterey County, California. Submitted to Monterey Peninsula Water Management District, Monterey.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1994. An Overview of the Esselen Indians of Central Monterey County, California. Coyote Press, Salinas.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1995a. Additional Archaeological Investigations Prepared as a Supplement to Phase II Cultural Resources Investigations for the New Los Padres Dam and Reservoir Project, Carmel Valley, Monterey County, California. Submitted to Monterey Peninsula Water Management District, Monterey.

Breschini, G.S. and T. Haversat. 1995b. Archaeological Evaluation of CA-MNT-234, at the Site of the Proposed Moss Landing Marine Laboratory, Moss Landing, Monterey County, California. Submitted to ABA Consultants, Capitola.

Breschini, G.S., T. Haversat, and J. Erlandson. 1996. California Radiocarbon Dates. Eighth Edition. Coyote Press, Salinas.

Breschini, G.S., T. Haversat, and R.P. Hampson. 1983. A Cultural Resources Overview of the Coast and Coast-Valley Study Areas [California]. Submitted to the Bureau of Land Management, Bakersfield.

Cook, S.F. 1974a. The Esselen: Territory, Villages, and Population. Monterey County Archaeological Society Quarterly 3(2).

Cook, S.F. 1974b. The Esselen: Language and Culture. Monterey County Archaeological Society Quarterly 3(3).

Dixon, Roland B. and Alfred L. Kroeber. 1913. New Linguistic Families in California. American Anthropologist 15(4):647-655.

Dixon, Roland B. and Alfred L. Kroeber. 1919. Linguistic Families in California. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 16(3).

Edwards, R.L., G.S. Breschini, T. Haversat, and C. Simpson-Smith. 1997. Archaeological Evaluation of Sites CA-MNT-798, CA-MNT-799 and CA-MNT-800, in the Pfeiffer Beach Day Use Area, Big Sur, Monterey County, California. Coyote Press Archives of California Prehistory 48.

Elsasser, A. B. 1978. Development of Regional Prehistoric Cultures. In Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 8, California, pp. 37-57. William G. Sturtevant, general editor. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Fenenga, G.L. 1988. An Analysis of the Shell Beads and Ornaments from CA-MNT-33a, Carmel Valley, Monterey County, California. In Analyses of South-Central California Shell Artifacts, Gary S. Breschini and Trudy Haversat, eds. Coyote Press Archives of California Prehistory 23:87-106.

Gerow, B. A. 1974. Co-traditions and Covergent Trends in Prehistoric California. Occasional Papers of the San Luis Obispo County Archaeological Society 8.

Gerow, B.A. (with R.B. Force).1968. An Analysis of the University Village Complex with a Reappraisal of Central California Archaeology. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Haversat, T. and G.S. Breschini. 1984. New Interpretations in South Coast Ranges Prehistory. Paper presented at the Annual Northern Data Sharing Meeting of the Society for California Archaeology, Aptos.

Hester, T. R. 1978. Esselen. In Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 8, California, pp. 496-499. William G. Sturtevant, general editor. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Hopkins, N.A. 1965. Great Basin Prehistory and Uto-Aztecan. American Antiquity 31(1):48-60.

Hylkema, M.G. 1991. Prehistoric Native American Adaptations along the Central California Coast of San Mateo and Santa Cruz Counties. Master's thesis, San Jose State University.

Jones, T.L. 1994. Archaeological Testing and Salvage at CA-MNT-63, CA-MNT-73, and CA-MNT-376, on the Big Sur Coast, Monterey County, California. Ms. on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, Monterey.

Jones, T.L. 1995. Transitions in Prehistoric Diet, Mobility, Exchange, and Social Organization along California's Big Sur Coast. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Davis.

Klimek, S. 1935. Culture Element Distributions, I: The Structure of California Indian Culture. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 37(1):1-70.

Krantz, G.S. 1977. The Peopling of Western North America. In: Method and Theory in California Archaeology. Occasional Papers of the Society for California Archaeology 1.

Kroeber, A.L. 1904. The Languages of the Coast of California South of San Francisco. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 2(2).

Kroeber, A.L. 1923. The History of Native Culture in California. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 20(8).

Kroeber, A.L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 78.

Lathrap, D.W. and R. C. Troike. 1988. Californian Historical Linguistics and Archaeology. In: Archaeology and Linguistics, A. M. Mester and C. McEwan, eds. Journal of the Steward Anthropological Society 15(1&2):99-157.

Levy, R. 1978. Costanoan. In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 8, California, pp. 485-495, R.F. Heizer, vol. ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Levy, R. 1997. The Linguistic Prehistory of Central California: Historical Linguistics and Culture Process. In: Contributions to the Linguistic Prehistory of Central and Baja California. Coyote Press Archives of California Prehistory 44:127-141, 1997.

Milliken, R. 1981. Ethnohistory of the Rumsen: The Mission Period. In: Report of Archaeological Excavations at Nineteen Archaeological Sites for the Stage 1 Pacific Grove-Monterey Consolidation Project Regional Sewerage System, S.A. Dietz and T.L. Jackson, eds. Four volumes. Submitted to State Water Resources Control Board, Sacramento.

Milliken, R. 1987. Ethnohistory of the Rumsen. Papers in Northern California Anthropology 2. Northern California Anthropological Group, Berkeley.

Milliken, R. 1991. Ethnography and Ethnohistory of the Big Sur District, California State Park System, During the 1770-1810 Time Period. Submitted to Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Milliken, R. 1992. Ethnographic and Ethnohistoric Background for the San Francisquito Flat Vicinity, Carmel Valley, Monterey County, California. Appendix 2 in: Baseline Archaeological Studies at Rancho San Carlos, Carmel Valley, Monterey County, California, by Gary S. Breschini and Trudy Haversat. Coyote Press Archives of California Prehistory 36:144-173.

Moratto, M.J. 1984. California Archaeology. Academic Press, Orlando.

Pritchard, W.E. 1968. Preliminary Excavations at El Castillo, Presidio of Monterey, Monterey, California. Central California Archaeological Foundation, Sacramento.

Pritchard, W.E. 1984. Preliminary Archaeological Investigations at CA-MNT-101, Monterey, California. Coyote Press Archives of California Prehistory 3:1-42.

Sapir, E. 1917. The Position of Yana in the Hokan Stock. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 13(1).

Shaul, D.L. 1988. Esselen Linguistic Prehistory. In: Archaeology and Linguistics, A.M. Mester and C. McEwan, eds. Journal of the Steward Anthropological Society 15(1&2):47-58.

Taylor, W.W. 1961. Archaeology and Language in Western North America. American Antiquity 27:71-81.