This report details the methods utilized and summarizes the results obtained from limited test excavations at archaeological site CA-FRE-1333, a small rockshelter and associated midden located in the White Creek area of western Fresno County, California. The excavations were conducted by Archaeological Consulting during September of 1986 under contract CA950-CT6-30, issued by the Bureau of Land Management, Sacramento.

The contract required that we assess the extent of past impacts to the site, evaluate its significance, and develop management recommendations for the protection of the site. As a part of this process, the contract required mapping of the site, excavation of at least four 1 x 1 meter archaeological units, analysis of the materials recovered, preparation of a final report, and curation of the recovered materials.

PROJECT LOCATION AND SETTING

Archaeological site CA-FRE-1333 is located within a small side canyon adjacent to White Creek, in the Diablo Range about 40 km northwest of Coalinga, in western Fresno County, California (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Project Vicinity Map.

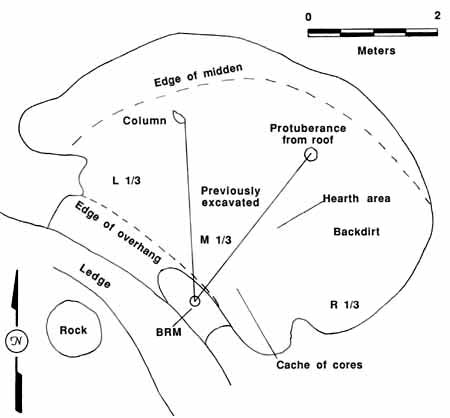

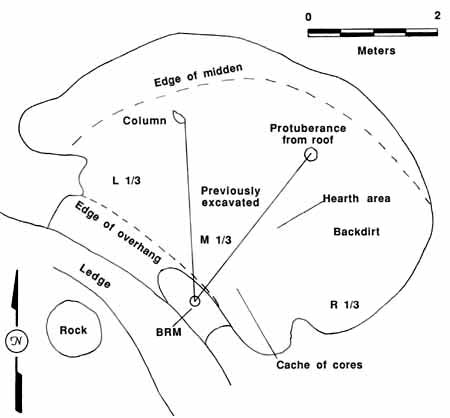

CA-FRE-1333 is situated on a south-facing slope overlooking a small drainage which enters White Creek from the northwest. The site is at an elevation of 2,360 feet, approximately 60-80 feet above the level of White Creek. The cultural material is located both within and below a sandstone outcrop containing several small rockshelters (Figure 2).

The site's dimensions are approximately 30 meters north-south (up and down the slope), and 20 meters east-west along the sloping hillside. There is a primary concentration of midden below Rockshelter B, with slope wash extending down the slope nearly to the drainage. Cultural materials were also present in Rockshelter C, and in extremely small quantities in Rockshelter B.

Figure 2. Site Map.

Environmental Setting

The White Creek area apparently received its name from the white stains found on the rocks in the creek channel. This stain reportedly comes from asbestos and other dissolved minerals in the water. Portions of the White Creek area to the north of CA-FRE-1333 are currently within an asbestos hazard area. The White Creek area now known to be within the endemic area for Valley Fever (coccidioidomycosis), caused by the fungus (mold) Coccidioides immitis (cf. Loofbourow and Pappagianis 1981). In spite of using dust masks, all crew members on the project who were not immune from a previous episode contracted the infection within three weeks.

Physiographic Setting

Site CA-FRE-1333 is situated within the Diablo Range, between the Salinas and San Joaquin Valleys. This somewhat rugged interior mountain range has elevations to 5,241 feet (San Benito Mountain, approximately 10 km northwest of the study area). The area is characterized by generally steep mountains with narrow valleys.

Water Resources

The nearest potential water source to CA-FRE-1333 is a small unnamed drainage just below the site. At the time of the test excavation (September 1986), this drainage contained no water. White Creek, approximately 300 meters away, is considered an intermittent water source but was running well at the time of the project, and small minnows occasionally were seen. There are also several scattered springs known in the general area. Based on the number of archaeological sites in the area, water must have been relatively abundant for part or most of the year.

Climate

The diurnal range within the interior mountains can be two or three times as great as that found on the coast. While the diurnal range at Piedras Blancas, on the coast in northern San Luis Obispo County, is about 11 degrees, at Priest Valley, some 12.5 km southwest of the project area the diurnal range is 36 degrees F. At Priest Valley the mean low and high temperatures are 35 and 71 degrees F, with a record mean of 53 degrees F. The record mean precipitation is 19.58 inches, and the average growing season is only 128 days (Felton 1965:52). However, the White Creek area is on the east side of the Diablo Range, while Priest Valley is on the west. Rainfall in the project area may be somewhat less than at Priest Valley. In general the area is characterized by hot and dry summers, mild to cold winters, and modest rainfall.

Plate 1. View of CA-FRE-1333 from the Adjacent Hillside. View is to the northeast.

Vegetation Communities

According to Küchler's (1977) vegetation map, the White Creek area is located within the blue oak-digger pine forest vegetation community. This community is described by Küchler as follows:

Blue Oak-Digger Pine Forest (Pinus-Quercus)

Structure: Medium tall, dense to open broad-leaved deciduous forest with an admixture of needle-leaved evergreen trees. Low broad-leaved evergreen trees and/or shrubs are common. Near the California Prairie the canopy opens up, the prairie forms a continuous ground cover, and the forest changes into a savanna. Inclusions of chaparral may be numerous.

Dominants: Digger pine (Pinus sabiniana), blue oak (Quercus douglasii)

Location: Distributed mainly in a belt of varying width around the Central Valley [Küchler 1977:926.]

As noted above, inclusions of chaparral may be numerous. In fact, CA-FRE-1333 is located within one such inclusion. The chaparral community is described by Küchler as follows:

Chaparral (Adenostoma-Arctostaphylos-Ceanothus)

Structure: Dense communities of needle-leaved and broad-leaved evergreen sclerophyll shrubs, varying in height from 1-3 m, rarely to 5 m. An understory is usually lacking. Inclusions of southern oak forest are common in the coastal regions of Santa Barbara to San Diego counties in canyons and other drainage areas and on clay.

Dominants: Chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum), manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.), California lilac (Ceanothus spp.)

Location: Lower elevations of most mountain ranges but absent in plains, desert and high elevations [Küchler 1977:927-928].

CULTURAL BACKGROUND

The following sections present discussions of previous archaeological investigations at CA-FRE-1333, previous investigations in the region, the existing regional sequence within the western or northern San Joaquin Valley, and the ethnographic background of the general project area.

Previous Archaeological Investigations at CA-FRE-1333

Archaeological site CA-FRE-1333 was first recorded on May 22, 1980, by Jim Woodward, who was conducting a cultural resource reconnaissance for the Bureau of Land Management. The archaeological site record completed by Woodward described the site as "a double-chambered rockshelter at the base of a sandstone cliff." Woodward noted that illegal excavation, with window screen and shovels, had taken place in the rockshelter.

Woodward described the site as follows (the smaller shelter has now been designated Rockshelter B, and the larger one Rockshelter C; see Figure 2):

Exposure of the rockshelters is SW so they do not get the morning sun. The larger rockshelter has (or had) a substantial midden deposit which has been heavily damaged and screened by relic hunters. The deposit covered at least 12' of the 28' width and at least 10' of the 15' of depth. The depth of the deposit is unknown, though the vandal pit exceeds 40 cm. Three bedrock mortars are present on a low sandstone ledge framing the mouth of the larger rockshelter. A few flakes were found in both shelters, but the majority of lithic material is in front of the smaller rockshelter extending 80' SW on a 50% slope. The larger shelter is full of rodent nesting and waste material. Some burned bone fragments and shell (not abalone) were found there. Cores of red, brown, and green chert were found inside. Many areas have a fire-blackened ceiling. The brown, sandy soil includes ash and charcoal.

The astern, smaller rockshelter contains a large amount of burned pine nut shells, Juniper seeds (probably rodent caches), and a few chert flakes--ink, white, and blue. The sandy brown deposit is only 15 to 25 cm deep but contains ash, charcoal, and small amounts of pink bone fragments (deer?). Very little rockfall or disturbance was apparent in the smaller rockshelter [Site Record, page 2].

No report was ever completed on the reconnaissance (Jim Woodward, personal communication 1986), but detailed site records, including numerous photographs, were prepared and were valuable during the current project.

Additional background also is provided in the Clear Creek Management Plan and Decision Record (U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management 1986). In the latter document, CA-FRE-1333 is described as follows:

This site consists of a rockshelter containing a substantial midden deposit with numerous artifacts. Although this site has been heavily impacted by pothunters, much of the deposit still remains. Cultural material noted includes a high density of chert flakes, burned bone, several tools, shell (some abalone), and fire-affected rock. Several bedrock mortars are located at the shelter entrance [U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management 1986:23].

Two 1 x 1 meter test pits were excavated at CA-FRE-1333 by BLM archaeologists Bruce Crespin and Don Manuel in September of 1980. Test Pit 1 (TP1) was excavated by Don Manuel within the primary midden in front of Rockshelter B, while Test Pit 2 (TP2) was excavated by Bruce Crespin within Rockshelter C. A small collection of materials was stored at the Hollister office of the Bureau of Land Management--usable portions of this collection have been incorporated into the current study. No report could be located on the excavations, although Don Manuel stated that he prepared a draft report based on field notes while he was at the Folsom office (personal communication 1986).

Test Pit 2, in Rockshelter C, showed a minimal depth (nowhere more than about 35 cm). Very few materials were collected from this unit (Bruce Crespin, personal communication 1986).

Plate 2. Exterior View of Rockshelter C (Unit 2). View is to the northeast.

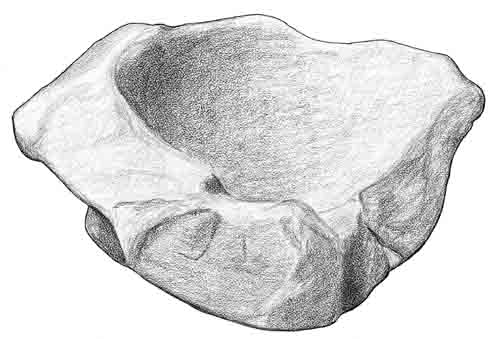

Test Pit 1 was situated an the western side of the primary midden deposit below Rockshelter B. Our Unit 3 was placed so as to include the eastern edge of this unit (Figure 2), as evidenced by soil slumping. Don Manuel notes that the unit encountered an inverted bowl mortar 30 cm or larger in size at approximately 40 cm. When the mortar was removed, a flexed burial, identified only as an adult, was exposed. Don Manuel recalls that the unit was abandoned at this point. (The mortar was collected and curated at the Hollister office. It has been incorporated into the collection from this project.) Several flaked stone artifacts also were recovered from this test pit, and Don Manuel has a vague recollection of finding several shell beads (Don Manuel, personal communication 1986). Three flaked stone artifacts were included within the collection stored at the Hollister office, as were one Olivella shell and one stone bead. All of these artifacts are included within the collection from this project, and are addressed in subsequent sections.

Previous Archaeological Investigations in the Region

There have been very few archaeological investigations within the general project area. Other than the Woodward survey which covered a small portion of the White Creek area, only three other major surveys have been conducted within the immediate project area. These were Napton's Clear Creek and Juniper Ridge surveys, and Dallas' Martin Ranch survey. Also, a minor survey was conducted by Hewes and Massey, who visited the general vicinity in 1939.

In June of 1939, G.W. Hewes and W.C. Massey visited a site near the confluence of Los Gatos and Nunez Creeks, some 15 km southeast of the project area. This site was reported by a local resident to be 6 to 7 feet deep; numerous artifacts were collected and shipped to the Lowie Museum of Anthropology at U.C. Berkeley. They conducted extensive investigations in other portions of the Coalinga and Central San Joaquin Valley areas, but apparently came no closer to the current project area.

In 1975, Napton conducted an archaeological reconnaissance centering on the Clear Creek drainage in San Benito County approximately 15 km northwest of the current study area (Napton 1975). Portions of Picacho Creek and Byles Canyon also were examined. This area was probably within the territory of the Chalon Costanoans (Breschini, Haversat, and Hampson 1983:285). Fifteen archaeological sites of various kinds were recorded during the survey. Some of these sites, however, consisted of as little as a chert core (CA-SBN-67), a flake and a core (CA-SBN-60), and two flakes (CA-SBN-61). While only a few of the 15 sites contained evidence of occupation, the survey results suggest that the area was utilized to a moderate extent during prehistoric times.

A second survey, in the Juniper Ridge area to the south and southeast of the current study area, was conducted in 1976 (Napton and Greathouse 1977). The study area was approximately 23,680 acres, with 36 person-days spent in the field. A considerable amount of time appears to have been spent in travel to and from survey areas. This survey concentrated on Juniper Ridge, with most field examinations on the ridge itself or on the steep slopes on either side. Only two sites were located; both were near springs and were found during vehicle rather than pedestrian surveys. It was concluded "that the archaeological potential of the area is very low" (Napton and Greathouse 1977:57). However, based on the limited intensity of the survey, and the nature of the areas examined, this conclusion appears to be completely unjustified.

A recent partial survey of the 27,311 acre Martin Ranch, approximately 15 km northeast of the project area, covered approximately 1,463 acres (Dallas 1985). Fifteen prehistoric sites were recorded, many of which exhibited evidence of at least seasonal habitation. Like the Clear Creek survey, this project also indicates that there was a moderate amount of occupation within the Diablo Range in prehistoric times.

The only published archaeological excavations which are pertinent to the study area are those conducted for the Central Valley Water Project in the Panoche and San Luis Creek drainages (cf. Olsen and Payen 1968, 1969, 1983; Pritchard 1970, 1983; etc.). A brief overview of the data and a suggested cultural sequence are contained in Moratto (1984). A summary of the regional sequence for this area has also been presented by Haversat and Breschini (1985:29-54). Information from these discussions is presented below.

Regional Sequence

There are a number of archaeological cultures which tentatively have been identified within the western or northern San Joaquin Valley. Also, there are at least two cultural hiatuses posited for the region. Most of the data on the regional cultural sequence is available from three sources: Olsen and Payen (1969); Moratto, King, and Woolfenden (1978); and Moratto (1984). The cultural sequence tentatively identified in these sources is outlined and discussed below. However, these hypothesized cultures and hiatuses are based upon limited archaeological samples from a limited area; few sites have been tested, and many of these are either very poorly dated or have not been dated at all. The range of variation is also still little known.

These tentative cultures should be considered working hypotheses to be modified or even abandoned as new data become available. For example, as discussed below and as shown in Figure 11, we are proposing that some modifications be made in this sequence. These changes are suggested, in part, on the basis of data generated during the current project.

Fluted-Point Tradition

The earliest culture generally accepted for this part of California is the Fluted-Point Tradition. Fluted points have been found at Tulare Lake, some 75 km southeast of the study area (Riddell and Olsen 1969), near Tracy Lake to the north, and at CA-MER-215, in western Merced County. Moratto takes a conservative view of the age of the Fluted-Point Tradition in California, placing the beginnings at "roughly 12,000 years ago" (1984:88). He states:

Big-game hunting is one economic specialization linked to the fluting technology, but surely not the only one. Clovis-like points in the Far West occur in coastal, valley, pass, and lakeshore settings along with the remains of molluscs, birds, and both large and small mammals. No unequivocal big-game kill sites have been reported. These varied settings and faunal remains, coupled with a diversified toolkit, suggest a generalized hunting-gathering way of life. In California and the Great Basin the proximity of fluted points to old pluvial lakes is especially notable. It seems likely that in such areas the Fluted-Point Tradition peoples would have adapted increasingly to lake and marsh environments, gradually evolving into the Western Pluvial Lakes Tradition by circa 11,000 B.C. [Moratto 1984:88].

Western Pluvial Lakes Tradition

While the origins of the Western Pluvial Lakes Tradition are obscure, it could represent a direct outgrowth of the Fluted-Point Tradition. Along California's coast at about this same time is the Paleo-Coastal Tradition, and it is possible that this too evolved from the Fluted-Point Tradition (Moratto 1984:111). The Western Pluvial Lakes Tradition is still poorly defined in most areas, but probably flourished "from circa 11,000 B.P. until Altithermal climates led to the evaporation of the lakes, beginning approximately 8000 years ago" (Moratto 1984:103). Traits thought to characterize this tradition are summarized below:

1) A tendency for sites to be located on or near the shores of former pluvial lakes and marshes or along old stream channels.

2) Dependence on hunting various mammals, fowling, collecting, and gathering vegetal products.

3) An absence of ground-stone artifacts such as millingstones, hence a presumed lack of hard seeds in the diet.

4) A developed flaked-stone industry, marked especially by percussion-flaked foliate knives or points, Silver Lake and Lake Mojave points, lanceolate bifaces, and points similar to the long-stemmed variety from Lind Coulee [in central Washington].

5) Lastly, the . . . toolkit, which commonly includes chipped-stone crescents, large flake and core scrapers, choppers, scraper-planes, hammerstones, several types of cores, drills, and gravers, and diverse flakes [Moratto 1984:93].

Altithermal (Hiatus?)

Within the San Joaquin Valley there is virtually no evidence of archaeological cultures during the Altithermal (a hypothesized period of warmer and drier climate from about 7,500 to 5,250 years ago). While it is possible that some of the Buena Vista and Tulare Lake materials relate to this period, supporting radiocarbon dates are not yet available. It is also possible that sites from this and earlier periods in the San Joaquin Valley have been deeply buried by alluviation.

Positas Complex

The Positas Complex is currently represented only by the material at the base of CA-MER-S94, and is very tentatively linked to southern California on the basis of "doughnut stones" (Olsen and Payen 1969:41). This complex does not yet appear to fit with any of the other sites in the area. Tentative estimates for the age of this complex are 5,250-4,550 years ago (Moratto 1984:191; Olsen and Payen 1969). However two radiocarbon dates from the base of CA-MER-S94 not only fail to support the estimated age for this complex but disagree with each other as well (Haversat and Breschini 1985:41). Items which may be diagnostic of this period are:

. . . perforated, flat cobbles; a few flake scrapers; rare examples of small shaped mortars; short cylindrical pestles; and at least several milling slabs and mullers. Two or three deep projectile point fragments may belong here, but it is doubtful. Several other chipped stone objects (such as small plane scrapers) also could be associated with this complex. One Spire-Lopped Olivella bead and several perforated pebble pendants also occurred in the deep levels and could belong to the complex [Olsen and Payen 1969:41].

Pacheco B Complex

The Pacheco B Complex "is represented by only a few distinctive items which suggest a relationship to the Central California Early period" (Olsen and Payen 1969:41). Potentially diagnostic elements of this period, tentatively dated at 4,550-3,550 years ago (Moratto 1984:192) include the following:

. . . Thick, Rectangular Olivella beads, the rare occurrence of rectangular Haliotis or freshwater mussel shell beads, several large points and a few examples of heavy food-processing tools. Possibly, the graver-like tools and the large leaf-shaped biface point fragments belong here, also [Olsen and Payen 1969:41].

Pacheco A Complex

According to Olsen and Payen, the Pacheco A Complex "marks an incursion of coastal people to the west edge of the valley" (1969:41). This is based partially on the discovery of flexed burials at a time when extended burials were prevalent in the Central Valley. Potentially diagnostic elements of the Pacheco A Complex, which tentatively is dated from 3,550-1,650 years ago (Moratto 1984:192) are listed below:

. . . Spire-ground; Modified Saddle (Type 3b2); Saucer (Type 3c); and Split-drilled (Type 3b1) (all of Olivella); and Macoma clam disc beads. One Haliotis disc bead and a few centrally perforated Haliotis cracherodii shell ornaments are known, as well as several rare stone bead types. These bead and ornament forms are clearly related to the Middle period in central California.

Distinctive bone artifacts include perforated canine teeth, bird bone whistles, a few crude bone awls, scapulae grass cutters with ground edges and a few other types of less diagnostic value. Large spatulate bone tools and various perforated "pin" forms do not occur, though they are distinctive in the Delta.

Polished stone objects include rings of slate and jade slate, pins and flat pebble pendants. These lack variety and are often poorly made.

Especially distinctive is the heavy stone tool complex. A variety of mortar and pestle forms occur. Milling slabs and mullers are frequent. Some of the latter are well made rectangular forms. All forms of grinding tools are especially abundant.

The projectile point complex includes large to medium silicate and obsidian points, frequently stemmed or side-notched. Almost all are percussion flaked and weigh from 3 to 10 gm. Some of the points, on the basis of form and material, certainly are derived from the coast, presumably the Monterey Bay area.

A limited number of other elements indicate contact to the west. These include fragments of Mytilus and clamshell in the midden, a Mytilus shell fishhook and possibly a fragmentary jade ring [Olsen and Payen 1969:40-41].

Gonzaga Complex

The late prehistoric occupation in the San Joaquin Valley has been termed the Gonzaga Complex. Olsen and Payen state that this occupation relates closely to the Late Period Phase 1 of the Delta region. Tentative dates are 1,650-950 years ago (Moratto 1984:192). Diagnostic elements are as follows:

The frequent Olivella bead forms include: Whole Spire-ground (Types 1a, 1b); Thin Centrally-perforated Rectangular (Type 2a1); Split-punched (Type 3a2); Oval; and several variant forms of the Thin Rectangular bead. Freshwater mussel shell disc beads and whole limpet shells (Megathura crenulata) also occurred. Haliotis shell ornaments (all Haliotis rufescens) of frequent occurrence include simple circular, oval and tear-drop shapes. Less frequent are forms with a flat end and round top of split "fishtail" end and round top. All types are frequently decorated with the distinctive X- or V-shaped incising on the edges. Specimens with bead applique' set in asphaltum are known, some of the discs have the convex surface smeared with asphaltum and may have served as ear-spool facings.

Projectile points are rare. One large squared stem and a large tapered stem point are definite occurrences along with fragments of large incipient serrated obsidian points from one component.

Bone items include a few awls, pins, incised mammal bone tubes, bird bone whistles and several scapulae grass cutters. Most of the latter have notched rather than ground edges. Polished stone objects include large spool-shaped ear ornaments and small cylindrical "plugs".

The heavy stone tools include large bowl mortars; shaped pestles; rare slab mortars; and the slab milling stone and muller. The latter are rarely shaped. The relative frequency of mortar versus the milling stone is not known from our excavated samples. It is clear, however, that the use of the milling stone and muller is more important here than in the later period, but less frequently than the preceding Pacheco complex [Olsen and Payen 1969:40].

Hiatus?

Based on research into prehistoric environments and culture change, some researchers have suggested a possible cultural hiatus between approximately 1,400 and 600 years ago (cf. Moratto, King, and Woolfenden 1978:155) or between approximately 950 and 450 years ago (Moratto 1984:193).

There is, however, little archaeological information from the western San Joaquin Valley to support this hypothesized cultural hiatus. For example, of 11 radiocarbon dates from western Merced County, three dates (from sites CA-MER-215 and CA-MER-S94) fall within this time period (Haversat and Breschini 1985:49; Breschini, Haversat, and Erlandson 1986:14). In addition, three of the four radiocarbon dates from the current project also fall within this time span.

From this evidence, it appears that there was not a cultural hiatus of the type and duration hypothesized for the west side of the San Joaquin Valley. It is most likely that the late period (represented by the hypothesized Gonzaga and Panoche Complexes) was continuous within the region, although localized abandonments and shifts certainly could have occurred.

Figure 11 presents an updated version of the hypothesized regional sequence. However, there still is insufficient evidence for us to modify the hypothesized cultures within the region, or to establish any firm dividing line between the hypothesized Gonzaga and Panoche Complexes. While it is likely that many additional changes will be necessary before this regional sequence is accurate, the data and the detailed research needed to make these changes are not yet available.

Panoche Complex

The protohistoric period along the west side of the San Joaquin Valley is known as the Panoche Complex, and dates from approximately 450 to 150 years ago. This falls within the Late Period Phase 2 of the Central California Taxonomic System. Diagnostic elements are as follows:

. . . rare clamshell disc beads; Tivela tubular clam beads; steatite disc beads; Haliotis epidermis disc beads; side-ground Olivella beads; spire-ground Olivella beads; small, thin Olivella discs (Type 3d); small, thick Olivella discs (Type 3e) (some incised); small, rough Olivella disc beads; and lipped Olivella beads. Haliotis ornaments are rare, but include simple circular, rectangular or "tabbed" end forms. Projectile points are usually of the small side-notched, concave-based tradition, termed "Panoche side-notched", along with rare desert side-notched or serrated obsidian points, small triangular concave-based and, rarely, large stemmed points. Especially distinctive is the abundance of well chipped flake scrapers. Bone objects include awls and scapulae grass cutters, incised bird bone tubes or whistles, short bone beads, and long awl or dagger-like pieces. Ground or polished stone objects include both small and large steatite ear spools, simple conical pipes, ground actinolite or slate pins and a variety of mortar and pestle forms. Presumably, bedrock mortars were also in use during this period. Use of the milling slab and muller is weakly attested; usually, the latter are unifacial cobbles. Steatite vessels are known, but rare, and vessel sherd arrowshaft straighteners are also known. One site also produced a number of sherds of a crude brown pottery [Olsen and Payen 1969:39].

Ethnographic Background

In his Handbook of Yokuts Indians (1977), Latta writes:

Since about 1790 there had been no Yokuts Indians along the West Side plains and foothills. They had been stripped from that entire territory . . . and taken to the Spanish Missions on the coast. The Yokuts who were brave enough to remain along the west bank of the San Joaquin River were exterminated in 1833 by an epidemic that swept that entire area [Latta 1977:xix].

In the maps in Latta's handbook, the current study area is placed on the edge of the Tache (also Tachi) Yokuts territory. Concerning the Tache, Kroeber writes:

The Tachi, Tadji, or Dachi . . . , the northernmost of the three Tulare Lake tribes, appear to have been one of the largest of all Yokuts divisions, and still survive to the number of some dozens. The Spanish frequently referred to the Tache, and a Laguna de Tache land grant survives on our maps. Their country was the tract from northern Tulare Lake and its inlet or outlet, Fish Slough, west to the Mount Diablo chain of the Coast Range, where they bordered the Salinan Indians. Here they wintered at Udjiu [Latta's Poza Chaná], downstream from Coalinga, and at Walna [Latta's Walnau], where the western hills approach the lake [Kroeber 1925:484].

There is very little known specifically about the Yokuts northwest of Coalinga. As Latta noted, there were no surviving Indians from the West Side when the earliest anthropologists began working in central California. Working with other Yokuts, some information which pertains to the West Side has been gathered, but it is fragmentary and second hand.

One note of importance to the current study concerns trade patterns. The village of Poza Chaná was an important trading center, and may have been used by Yokuts, Salinan, Chumash, and even Costanoan groups. Concerning this village Latta writes:

At Huron was Holón and five miles southwest was Údgeu, known to whites as the Poza Chaná. Poza Chaná has been given several spellings. Chaná is not Spanish, but either is French or Indian [Latta 1977:141].

From Yoimot, reportedly the last full blooded Chunut Yokuts from the northeast shore of Tulare Lake, Latta obtained a number of stories. Concerning Poza Chaná she stated:

The Indian traders used to meet at the Poza Chaná to trade with the coast Indians. Kahn-te was the oldest chief of the Tache I ever knew. He used to have charge of the trading. He told me all about it and taught me his song.

The bead and seashell traders from the coast met the Tache traders at Poza Chaná. The Tache and the other Indians would not let the people from the west come right up to the lake. They were afraid they would learn how to get things without trading.

Kahnte told me that his people used to trade off fish, kots [obsidian], salt grass salt, and some seeds. Sometimes they traded kuts [koots, soapstone] beads. They brought back shell beads and sea shells, traw-neck [abalone], cawm-sool [clam], and caw-sool [olivella or periwinkle]. Kahnte told me about a funny dried thing that one of his men got in a trade. I know now it was a star fish [Latta 1977:728-729].

One of the possible routes for the Costanoan Indians to have taken to reach Poza Chaná would have been through the White Creek area.

Additional details on the ethnography of the Yokuts Indians can be obtained from the standard reference works, including: Kroeber (1925); Gayton (1930, 1936, 1945, 1948); Latta (1949, 1977); Wallace (1978b, 1978c); and Silverstein (1978).

FIELD METHODS

Fieldwork for the project was conducted, under the direction of Gary S. Breschini, Ph.D., SOPA, Principal Investigator, and Trudy Haversat, M.A., SOPA, Project Manager and Co-principal Investigator, between September 15 and 20, 1986. The field crew consisted of R. Paul Hampson, SOPA, and Anna Runnings, M.A.

An initial site visit was made on September 5, 1986 by Gary S. Breschini, Trudy Haversat, and Don Lipp, the Bureau of Land Management's Hollister Resource Area archaeologist. An examination of the site area revealed that there are four primary rockshelters within the sandstone formation. These rockshelters were designated A through D (see Figure 2). Rockshelter C contained the only visible midden deposit. Probing revealed a depth of less than 40 cm. Rockshelters A and B, when examined and probed, were found to be no more than 10 to 15 cm deep, and contained no midden deposit. Rockshelter D, at the upper end of the site, was probed to a depth of approximately one meter. There was considerable rock (roof fall) in the soil of this rockshelter, but there was no visible evidence of a midden deposit. The area downslope from Rockshelter B (Figure 2 ) was found to contain a midden deposit. Probing suggested a rocky deposit with a minimum depth of at least 80 cm.

The contract required the excavation of at least four 1 x 1 meter archaeological units. Based on information gathered during the initial field visit, and examination of records and the small 1980 collection, the following approach was selected:

- Unit 1 was placed within Rockshelter D to determine whether any midden might be buried beneath the roof fall and eroding sands. This unit, designated Unit 1, was 1 x 1 meters in size.

- During the field inspection it was decided to excavate the entire main rockshelter (designated Rockshelter C) as a single archaeological unit. This decision was based on: 1) the extremely limited depth of the deposit, as documented by probing; and 2) the previous disturbance, both from pothunters and from a test pit excavated by BLM archaeologists Bruce Crespin and Don Manuel in 1980. The entire rockshelter was designated Unit 2. It measured approximately 3 x 5 meters in size.

- Finally, in order to sample the midden in front of Rockshelter B, two units were placed within that area. The first, designated Unit 3, was placed within the primary midden deposit just below Rockshelter B. This unit measured 75 x 150 cm. The second unit, designated Unit 4, was placed much lower on the slope and near the edge of the midden (Figure 2). It measured 75 x 200 cm.

Unit 1

Unit 1 was placed within Rockshelter D to determine whether this shelter contained cultural materials. No cultural materials were visible on the surface, but probing indicated that there was approximately one meter of soil mixed with roof fall in one area. A 1 x 1 m unit was established and excavated using shovel and hoe. The soil was not screened, and levels were not maintained. Large slabs of roof fall, often extending beyond the edge of the unit, were removed by hand. The unit reached a depth of 100 cm, at which point further excavation was prohibitively difficult because of the almost continuous roof fall. No cultural materials were noted anywhere within the unit or within Rockshelter D.

Unit 2

Unit 2 was excavated in three wedge-shaped sections. These were designated L 1/3 (left), M 1/3 (middle), and R 1/3 (right). The dividing lines between the three subdivisions extended from the single bedrock mortar (BRM) to the eastern edge of a column and from the BRM to the tip of a small protuberance extending downward from the roof (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Rockshelter C.

Plate 3. Interior View of Rockshelter C (Unit 2) Prior to Excavation. View is to the northeast.

The surface dimensions of the uneven cultural deposit in Rockshelter C (Unit 2) were approximately 300 by 500 cm. The average depth of the primary deposit, as determined by probing, ranged from about 15 to 35 cm, with the greatest depth under the backdirt pile left by the pothunter(s). The edges of the deposit were shallower. The bedrock mortar in Rockshelter C was also used as the main site datum.

Rockshelter C (Unit 2) was first cleaned of much of the packrat debris, which was discarded. The soils were excavated with a hand-held hoe, trowel, and whisk broom. All recovered soils were screened through 1/8 inch mesh portable shaker screens. All materials which did not pass through the screens, with the exception of bulk rock and obvious packrat debris, were bagged, labeled, and transported to the laboratory for washing and sorting.

Plate 4. View of Rockshelter C after Excavation of L 1/3. The soil in the foreground has been disturbed by a pothunter(s) and by excavation of a 1 x 1 meter unit by the BLM. The mound in the background contains backdirt from the pothunter excavations.

Units 3 and 4

Unit 3 was placed within the area of primary midden concentration below Rockshelters B and C. It measured 75 x 150 cm, and was placed with one edge overlapping Test Pit 1, excavated by Bruce Crespin and Don Manuel in 1980. Unit 4 was placed lower on the slope to determine the depth and nature of the midden slope wash. It measured 75 x 200 cm. Units 3 and 4 were both excavated using our standard field procedures, that is, 10 cm arbitrary contour levels, with all recovered soils screened through 1/8 inch mesh portable shaker screens. All materials which did not pass through the screens, except bulk rock, were bagged, labeled, and transported to the laboratory for washing and sorting.

Soil samples were recovered from each level of Unit 3 beginning with the 20-30 cm level. These were used for obtaining charcoal samples for radiocarbon dating, and for identification of small microconstituents which may have passed through the 1/8 inch mesh.

Plate 5. Unit 3 at 50 cm, Showing Burial 1. Burial 1 is in the northwest corner of the unit, protruding from the sidewall. Shovel cuts on the rock in the northern sidewall resulted from the 1980 BLM excavation. A small fire hearth was removed from the southern portion of the left 1/3 of the unit. This hearth was radiocarbon dated.

LABORATORY PROCEDURES

When the materials from the field excavations arrived in the laboratory they were immersed in a tub of water. The packrat debris was floated out and discarded. The remaining materials were then wet screened using 1/8 inch mesh. Following air drying on window screen, the materials were sorted in the laboratory.

The artifacts were removed, illustrated, and catalogued individually. The bone, lithics, shell, and other midden constituents were bagged by provenience and weighed. The lithic materials were submitted to Michael F. Rondeau and Vicki L. Rondeau, and the bone and egg shell was submitted to Paul E. Langenwalter II. Their reports are included as Appendices 1 and 2, and are summarized in the following section. The shell and stone beads were submitted to Robert O. Gibson for analysis. His observations are contained in Appendix 3.

Following analysis, the collection, including the materials from the 1980 test, were curated at the Department of Anthropology, Bakersfield College, 1801 Panorama Drive, Bakersfield, CA 93305.

RESULTS OF THE INVESTIGATIONS

Our investigations suggest that CA-FRE-1333 is a "two-component" site. Both components, however, are within the temporal/cultural period designated as "Late Horizon" by the Central California Taxonomic System (CCTS).

The deposit in Rockshelter C appears to represent the Late Period, Phase 2 and possibly Phase 3 (protohistoric) (L2 and L3). Use of the site during this period (circa 450 to 150 years B.P.) appears to have been limited. The rockshelter probably served as a small campsite, and most likely was visited only occasionally for shelter while gathering resources or passing through the area.

The primary midden sampled by Unit 3, and including Burials 1 and 2, appears to represent a Late Period Phase 1 (L1) deposit (circa 1500 to 450 years B.P.). During this period the site appears to have functioned as a small village or base camp. Additionally, there may have been a period between these two components during which the site was not utilized.

The following sections present the data upon which these conclusions are based.

Nature and Distribution of the Midden Deposit

Small amounts of midden and cultural materials were found within the main rockshelter (Rockshelter C, excavated as Unit 2). The primary midden deposit, however, was limited to a small area below Rockshelter B. This deposit, measuring approximately 5 x 7 meters, was sampled by Unit 3. Slope wash from the primary midden was found as much as 18 meters south of (below) the main midden concentration. Unit 4 was placed within this area.

The midden deposit removed from Rockshelter C contained evidence of the following: cooking or heating fires (including a small hearth area containing charcoal, burned soil, and fire-altered rock); bone; shell; lithics (including a possible cache of one core and two core fragments, and a modified flake); a bone awl fragment; three shell beads; and small quantities of egg shell, subsequently identified as vulture. The three shell beads were of Olivella and Haliotis, and appeared to be from Phase 2 of the Late Period. A single bedrock mortar is situated on a small bench at the mouth of the rockshelter. The 1980 site record reported three bedrock mortars, but two of these were judged to be of natural origin.

The primary midden deposit was situated on a small ledge below Rockshelter B. This area, which measured only about 5 x 7 meters, was approximately 100 cm in depth. The deposit was dark and ashy, and contained quantities of fire-altered or fire-broken rock. As shown by Unit 3, the deposit also included the following: considerable evidence of cooking or heating fires (including a small hearth area containing charcoal and fire-altered rock); human interment; bone and bone production waste; a sandstone mortar fragment; shell; small quantities of ochre; lithics (including an obsidian flake and various artifacts); two Olivella shell beads; and three Olivella shell fragments.

As shown by Unit 4, the area downslope from the primary midden contained less evidence of a midden deposit. Although there was more bone than in the primary midden, there was about the same quantity of lithic material (including a tiny obsidian flake). Several flaked stone artifacts and two bone tool fragments were recovered. However, the soil did not have the dark and ashy consistency, and contained much smaller quantities of charcoal and fire-altered or fire-broken rock. Other constituents were minimal, and included only a trace of shell and two tiny pieces of ochre. The depth of Unit 4 was only 50 cm, and that depth was reached only by digging out cracks in the rocky floor of the unit. One mano was found nearby during a surface examination.

Previous Disturbance

Previous deliberate disturbance of the midden deposit appears to be confined largely to the excavation by an unknown pothunter(s) in Rockshelter C (as attested by the screens found by Jim Woodward in 1980) and to the two 1 x 1 meter test pits excavated in 1980 by BLM archaeologists Bruce Crespin and Don Manuel. There also appears to have been some damage to the site from natural slope wash and slumping.

The main cave (Rockshelter C) was not as disturbed by pothunters as had originally been feared. The area in the center of the shelter (excavated as M 1/3) contained the most disturbance. This could be traced to some extent by the reworking and mixing of soils. There was a moderate amount of rodent disturbance, but rodent burrows could be traced and separated in most areas. However, the presence of charred rodent bone and feces in some samples suggested that rodents were residents of the cave in prehistoric times. This, and the presence of vulture egg shell, suggests that analysis of the bone in this shelter would not produce reliable results.

We do not believe that Rockshelter C contained a dry deposit. Stains which appeared to be calcium carbonate left from evaporation of standing water were evident in the lower portions of the rockshelter after the deposit had been removed.

One index of the disturbance to a midden is the amount of historical material present, particularly below the surface levels. At CA-FRE-1333, only three items resulting from historic disturbance were found during the excavations. One was a small (0.2 g) piece of white plastic found in the 10-20 cm level of Unit 3. It appears to have come from the handle of a bucket. String from TP1, excavated by Don Manuel in 1980, also was found in Unit 3. An iron spike was found on the surface of the unit--it probably derived from the BLM excavation as well.

Based on our investigations, it appears that there has been very little disturbance to the primary midden deposit in the area of Unit 3. While the deposit does not appear to be large, it does appear to be almost entirely intact.

Midden Constituents

The primary midden constituents at CA-FRE-1333 were bone, lithic materials (predominantly Franciscan chert), and charcoal. Rock, almost all sandstone roof fall, was ubiquitous; some had been fire-altered or fire-broken. Marine shell, ochre, and egg shells were found in trace amounts. These materials are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Vertebrate Animal Remains

The vertebrate animal remains were submitted to Paul E. Langenwalter II for analysis. The complete text of his report appears in Appendix 1. A brief summary has been included in the following section.

The Unit 2 (rockshelter) sample was found to be unsuitable for analysis. Not only have bats, mice, and wood rats live in the shelter, but it has been used in the past by vultures as a nesting site. These occupants would have added considerable bone from small and intermediate sized animals, resulting in considerable biasing of the sample. As a result, the vertebrate sample used in Langenwalter's study was limited to Units 3 and 4, with only selected remains used from Unit 2.

Langenwalter's study of Units 3 and 4 identified 16,432 specimens, most of which were the result of human procurement and utilization. The sample is subdivided by species, total specimens, and minimum number of individuals in Appendix 1. Most of the animals represented in the sample were probably procured in reasonably close proximity to the site using a limited set of tools and techniques.

Five fish bones also were found in the deposit, suggesting that fishing was not a significant activity at CA-FRE-1333. The fish bones were identified by Peter Schulz, of the California Department of Parks and Recreation. One was identified as a shark tooth, while the other four bones were from species available locally.

Based on a deer temporal bearing an antler base, occupation of the primary midden area of the site (a small village or base camp occupied during Phase 1 of the Late Period) included the late summer to fall, from approximately August to December. A second such temporal bone, from Rockshelter C (a temporary camp or shelter used during Phase 2 of the Late Period), suggests a winter (January through March) use of the site. These estimates are based upon only two specimens, so the possibility certainly exists that the site was used during other portions of the year.

Table 1. Vertebrate Remains Recovered at CA-FRE-1333

(all weights are in grams).

| Provenience | Unit 2* | Unit 3 | Unit 4 |

| 0-10 cm | --- | 70.3 | 206.0 |

| 10-20 cm | --- | 77.7 | 212.1 |

| 20-30 cm | --- | 110.8 | 94.8 |

| 30-40 cm | --- | 92.3 | 53.6 |

| 40-50 cm | --- | 60.8 | 21.8 |

| 50-60 cm | --- | 65.3 | --- |

| 60-70 cm | --- | 55.2 | --- |

| 70-80 cm | --- | 24.0 | --- |

| 80-90 cm | --- | 1.9 | --- |

| 90-100 cm | --- | 0.1 | --- |

| L 1/3 | 83.0 | --- | --- |

| M 1/3 | 168.4 | --- | --- |

| R 1/3 | 355.0 | --- | --- |

| Total | 606.4 | 558.4 | 588.3 |

* Unit 2 contained considerable quantities of bone probably not associated with the prehistoric deposit. Unit 3 was 75 x 150 cm in size; Unit 4 was 75 x 200 cm in size.

Flaked Stone

The flaked stone assemblage was submitted to Michael F. Rondeau and Vicki L. Rondeau of Rondeau Archaeological for analysis. The complete text of their analysis appears as Appendix 2.

The lithic analysis documented a surprising range of formal lithic artifacts and debitage types. First, it appears that flaked stone came to CA-FRE-1333 in a variety of forms. However, the vast majority of the flaked stone was Franciscan chert. The reduction of cores was accomplished by direct free-hand percussion. The manufacture and use of bifaces ranged from initial edge trimming of flakes by percussion, early thinning stages by percussion, finishing of projectile points by pressure flaking, and finally reworking or discarding of broken points. The uniface fragment and the modified flakes suggest additional maintenance and manufacturing activities common to larger base camps and village sites. Finally, edge damage on the tools is extensive--crushing of the working edges precluded the retention of rounding. This type of crushing has not previously been observed by Rondeau and Rondeau. In summary, the range of behaviors suggested by the assemblage appears to be greater than that expected to have occurred during temporary occupation such as at a hunting camp.

>br>

Table 2. Flaked Stone Recovered at CA-FRE-1333

(all weights are in grams).

| Provenience | Unit 2* | Unit 3 | Unit 4 |

| 0-10 cm | --- | 42.8 | 39.8 |

| 10-20 cm | --- | 16.7 | 30.0 |

| 20-30 cm | --- | 18.9 | 14.3 |

| 30-40 cm | --- | 17.9 | 30.4 |

| 40-50 cm | --- | 17.3 | 14.4 |

| 50-60 cm | --- | 6.4 | --- |

| 60-70 cm | --- | 28.1 | --- |

| 70-80 cm | --- | 12.5 | --- |

| 80-90 cm | --- | 0.1 | --- |

| 90-100 cm | --- | 0.1 | --- |

| L 1/3 | 51.2 | --- | --- |

| M 1/3 | 32.7 | --- | --- |

| R 1/3 | 457.0* | --- | --- |

| Total | 540.9 | 160.8 | 128.9 |

* Includes three cores found together in a possible cache. Unit 3 was 75 x 150 cm in size; Unit 4 was 75 x 200 cm in size.

Charcoal

Charcoal was recovered from all levels of the deposit in Units 2 and 3. Small quantities of charcoal also were present in Unit 4. After lithic debris and bone, charcoal was the next most frequent midden constituent, suggesting that a considerable amount of burning and/or cooking has taken place at the site.

Shellfish Remains

Only small amounts (3.6 grams) of shellfish remains were recovered from the deposit. The amounts are quantified in Table 3 below, and the species represented are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Table 3. Shellfish Remains Recovered at CA-FRE-1333

(all weights are in grams).

| Provenience | Unit 2* | Unit 3 | Unit 4 |

| 0-10 cm | --- | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| 10-20 cm | --- | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| 20-30 cm | --- | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| 30-40 cm | --- | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| 40-50 cm | --- | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| 50-60 cm | --- | 0.0 | --- |

| 60-70 cm | --- | 0.0 | --- |

| 70-80 cm | --- | 0.0 | --- |

| 80-90 cm | --- | 0.0 | --- |

| 90-100 cm | --- | 0.0 | --- |

| L 1/3 | 0.1 | --- | --- |

| M 1/3 | 0.1 | --- | --- |

| R 1/3 | 2.0 | --- | --- |

| Total | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 |

Unit 3 was 75 x 150 cm in size; Unit 4 was 75 x 200 cm in size.

The shellfish fragments which could be identified are as follows (listed in the approximate order of frequency): abalone (Haliotis rufescens); sea urchin; mussel (Mytilus); clam; and Olivella. Many of the fragments recovered, however, were too small to identify.

Of those species which could be identified, abalone and sea urchin were dominant. Three small pieces of red abalone from Unit 2, R 1/3 comprised virtually all of the sample from that provenience, and approximately half of the entire sample from the site. Sea urchin was identified in at least four of the levels of Unit 3, with at least two different individuals probably being represented (based upon the size of the test fragments). Sea urchin remains also were recovered during the 1980 excavation. Three small fragments of Olivella shell were recovered from Unit 3. These could represent bead blanks, bead refuse, or could have been a fragment of a bead associated with Burial 1 (see below). Other shellfish species were present only in extremely small quantities.

Rock and Thermally-Altered Rock

Quantities of rock, primarily sandstone from roof fall, were found throughout the entire site and adjacent areas. Some of the rock had been fire-altered or fire-broken, particularly in the area of the primary midden and on the slope below. Several fire-altered rocks were found in the hearth feature in Unit 2, and portions of the rockshelter floor, both in the hearth area and near the entrance, exhibited fire reddening.

Other Materials

Only two other materials, ochre and egg shell, were found in the deposit. Very small quantities of red and yellow ochre were found in Units 3 (0.2 g) and 4 (1.7 g). Approximately 30 g of egg shell was found in Unit 2, with the largest quantities in the R 1/3. This was identified by Paul E. Langenwalter II as vulture, suggesting use of the rockshelter as a nesting site (see Appendix 1).

Features

Four features were found during the excavations. These were two fire hearths or concentrations, and two burials. These are discussed in the following sections.

Feature 1

One fire concentration was encountered in Rockshelter C, R 1/3. This consisted of a small area (ca. 25 x 25 cm) which contained concentrations of charcoal, what appeared to be burned soil, and several small fire-altered rocks. This was designated Feature 1.

This area was profiled, and obvious rodent burrows were cleaned out. The soil containing the feature was removed in a block and transported to the laboratory. This sample was not washed or screened. It was carefully examined, but other than higher concentrations of charcoal, no unusual midden constituents or concentrations of constituents were noted. The charcoal was subsequently used for a radiocarbon sample, and returned a date of 280 years B.P. (see below).

Feature 2

A second hearth feature, consisting only of several fire-altered rocks and a concentration of charcoal, was identified in the western third of Unit 3 at 40-45 cm. Although Burial 1 was located in this same general area, the two features did not overlap. The charcoal was carefully removed from the feature and bagged. It subsequently was used as a radiocarbon sample, and returned a date of 755 B.P.

Burial 1

Burial 1 was encountered in the 40-50 cm level of Unit 3. This is the same burial encountered by Crespin and Manuel during their 1980 test. As we placed Unit 3 to intersect only the eastern edge of their TP1, only a small portion of the burial was encountered. The burial was described by Don Manuel as being that of an adult, and was reported to be in a flexed position (personal communication 1986).

The few bones exposed were examined by Gary S. Breschini and Trudy Haversat, both qualified physical anthropologists. The bones included only fragments of the scapula, fibula, ulna, radius, humerus, and femur. The burial posture could not be determined. It was determined that the bones were from a full adult, possibly from a female. Given the bones present, the sex estimation was based upon the relative robusticity and size of the bones. Following this cursory examination, the area surrounding and beneath the burial was omitted from the unit. This reduced the size of the unit to approximately 75 x 110 cm rather than the original 75 x 150 cm.

One of the Olivella shell beads (Cat. no. 3) and the largest Olivella shell fragment (Cat. no. 4) were found in the 20-30 cm level of Unit 3. It is possible that they originally were associated with the burial, and had been disturbed by the 1980 excavation or by rodents. A second Olivella bead was found in the 50-60 cm level (Cat. no. 5). It too could originally have been associated with the burial. The two Olivella beads are of the same type (G2a), and date to approximately 950-450 B.P. Based on the radiocarbon date of 755 B.P. from the same level, the burial, which would have been intrusive, probably dates to the more recent end of this range.

Burial 2

Burial 2 was encountered in the floor of the 70-80 cm level of Unit 3, in the southeastern corner of the unit. This burial had not previously been disturbed. Bones identified included fragments of the tibia, humerus, scapula, radius, and possibly portions of a second humerus, as well as several unfused epiphyseal caps. It was estimated on the basis of the size and epiphyseal fusion that the individual was approximately two years of age. No estimation of sex could be made, and no burial posture could be determined as not enough of the burial was exposed.

A radiocarbon sample from the same level as the burial dated to 1420 B.P. Because the burial would have been intrusive, it should date considerably younger, probably to 1000 B.P. or less.

From the 80 cm level the area of Burial 2 also was avoided. The resulting unit, which was reduced in size to avoid Burial 1 and several large rocks, was thus reduced to less than 50 x 50 cm.

Artifacts

One artifact was collected from the surface by Jim Woodward when the site was first examined, six additional artifacts were recovered during the 1980 excavations, and 27 artifacts were recovered during the 1986 investigations. These are listed in Table 4, and discussed in more detail either in the following sections or in the appendices.

Shell Beads

The shell beads recovered from CA-FRE-1333 (Figure 4) were examined by R.O. Gibson. The complete text of his analysis appears as Appendix 3 of this report.

Figure 4. Shell and Stone Beads from CA-FRE-1333. 1. Haliotis epidermis disc bead. 2. Olivella Type G4 Bead. 3. Olivella Type G2a Bead. 4. Olivella wall fragment (bead blank?). 5. Olivella Type G2a bead. 17. Olivella Type E1a bead. 18. Stone cylinder. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Figure 4. Shell and Stone Beads from CA-FRE-1333. 1. Haliotis epidermis disc bead. 2. Olivella Type G4 Bead. 3. Olivella Type G2a Bead. 4. Olivella wall fragment (bead blank?). 5. Olivella Type G2a bead. 17. Olivella Type E1a bead. 18. Stone cylinder. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

In brief, Gibson determined that both status and economic monetary beads are present at CA-FRE-1333. The forms identified were in common usage both to the north and south of the site. Temporally the beads fall within Phases 1 and 2 of the Late Period, an estimate which is in close agreement with the four radiocarbon dates. Finally, three small wall fragments of Olivella shell were recovered from Unit 3. All were badly burned. These could represent bead blanks or fragments from bead manufacture, although other evidence of bead manufacture was absent.

Stone Bead

A single stone cylinder (bead) (Cat. no. 18) was recovered from CA-FRE-1333 during the 1980 excavation (Figure 4). This artifact was a part of the small collection provided to us by BLM's Hollister District Office. Unfortunately, however, no information could be located on the provenience of this artifact. Because it came from the 1980 excavation, it almost certainly came from either TP1 or TP2.

This bead also was examined by R.O. Gibson. Gibson estimates that it was fashioned from a light-colored green talc schist. While no specific temporal association can be assigned to this artifact, its form is very suggestive of Phase 2 of the Late Period.

Flaked Stone Artifacts

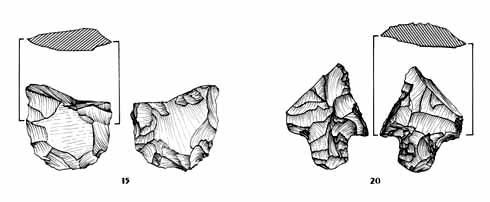

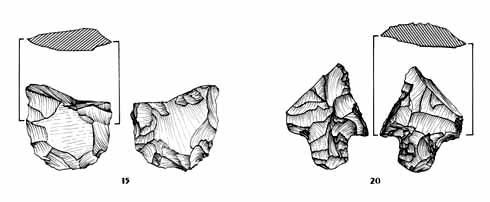

In the three investigations at CA-FRE-1333 to date, six projectile point fragments have been recovered. One was recovered from the surface by Jim Woodward when the site was first recorded (Cat. no. 20; Figure 5). A second (Cat. no. 16; Figure 6) was recovered by Bruce Crespin and Don Manuel during their 1980 test excavation. Four were recovered during the current investigations (Cat. nos. 8, 21, 23, and 24). The first of these (Figure 6) is a basal fragment, while the other three (not illustrated) are very small fragments (¾ 1.5 g).

Three biface fragments also were recovered. Two were recovered from TP1 during the 1980 excavation (Cat. nos. 14 and 15; see Figures 6 and 5). The third was recovered from Unit 4, 0-10 cm (Cat. no. 22, not illustrated).

Figure 5. Flaked Stone Artifacts from CA-FRE-1333. 15. Biface fragment. 20. Projectile point fragment. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Figure 5. Flaked Stone Artifacts from CA-FRE-1333. 15. Biface fragment. 20. Projectile point fragment. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Figure 6. Flaked Stone Artifacts from CA-FRE-1333. 14. Biface fragment. 16. Projectile point fragment. 8. Projectile point fragment. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Figure 6. Flaked Stone Artifacts from CA-FRE-1333. 14. Biface fragment. 16. Projectile point fragment. 8. Projectile point fragment. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

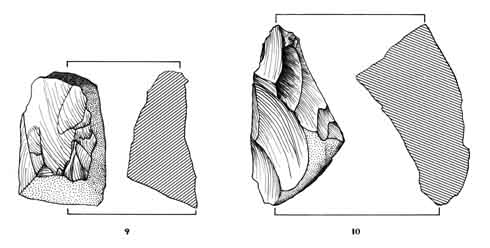

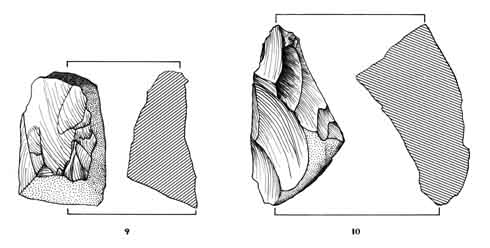

Five cores or core fragments were recovered during the current investigations. These included a possible cache of three well-prepared specimens (Cat. nos. 9, 10, and 11) from the R 1/3 of Unit 2 (Figures 8 and 9). A fourth core fragment (Cat. no. 12; Figure 7) was found nearby, but not in association. A fifth core specimen (Cat. no. 25; Figure 7) was found in Unit 4, 20-30 cm. If the small sample which was recovered has provided an accurate assessment of the materials present, then it appears that cores were more important at CA-FRE-1333 during Phase 2 of the Late Period than earlier. Perhaps during Phase 1 cores more often were reduced elsewhere and the intermediate products brought to the site.

Figure 7. Flaked Stone Artifacts from CA-FRE-1333. 7. Modified flake. 29. Core platform rejuvenation flake. 25. Core fragment. 12. Core fragment. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Figure 7. Flaked Stone Artifacts from CA-FRE-1333. 7. Modified flake. 29. Core platform rejuvenation flake. 25. Core fragment. 12. Core fragment. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Figure 8. Cores from CA-FRE-1333. 9. Core fragment. 10. Core. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Figure 8. Cores from CA-FRE-1333. 9. Core fragment. 10. Core. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Table 4. Artifacts Recovered from CA-FRE-1333.

| Cat. no. | Description | Provenience | Comments |

| 1 | Haliotis bead | Unit 2, L 1/3 | Epidermis disc |

| 2 | Olivella bead | Unit 2, R 1/3 | Type G4 |

| 3 | Olivella bead | Unit 3, 20-30 cm | Type G2a |

| 4 | Olivella wall frag. | Unit 3, 20-30 cm | Bead blank? |

| 5 | Olivella bead | Unit 3, 50-60 cm | Type G2a |

| 6 | Bone awl frag. | Unit 2, M 1/3 | -- |

| 7 | Modified flake | Unit 2, R 1/3 | Bifacial modification |

| 8 | Projectile point frag. | Unit 3, 70 cm | Basal fragment |

| 9 | Core frag. | Unit 2, R 1/3 | Part of cache? |

| 10 | Core | Unit 2, R 1/3 | Part of cache? |

| 11 | Core frag. | Unit 2, R 1/3 | Part of cache? |

| 12 | Core frag. | Unit 2, R 1/3 | Isolated |

| 13 | Mano | Surface, downslope | -- |

| 14 | Biface frag. | Test Pit 1 | Broken while thinning? |

| 15 | Biface frag. | Test Pit 1, 40-? cm | Limited reworking |

| 16 | Projectile point frag. | Test Pit 1, 40-? cm | -- |

| 17 | Olivella bead | Test Pit 2, 20-40 cm | BLM No. 19-8.1; Type E1a |

| 18 | Stone cylinder | Unknown | BLM No. 19-8.2 |

| 19 | Mortar bowl frag. | Test Pit 1, 40 cm? | BLM No. 19-8.3 |

| 20 | Projectile point frag. | Surface | BLM No. 19-8.4; broken and reworked? |

| 21 | Projectile point frag. | Unit 3, 0-10 cm | -- |

| 22 | Biface frag. | Unit 4, 0-10 cm | Percussion flaked |

| 23 | Projectile point frag. | Unit 4, 0-10 cm | Basal grinding? |

| 24 | Projectile point frag. | Unit 4, 10-20 cm | -- |

| 25 | Core frag. | Unit 4, 20-30 cm | Expended core? |

| 26 | Uniface frag. | Unit 3, 0-10 cm | -- |

| 27 | Modified flake | Unit 3, 40-50 cm | One edge modified |

| 28 | Modified flake | Unit 3, 40-50 cm | Two edges and tip modified |

| 29 | Core platform rej. flake | Unit 3, 40-50 cm | No modification |

| 30 | Uniface retouch flake | Unit 4, 20-30 cm | Edge crushing |

| 31 | Uniface retouch flake | Unit 4, 0-10 cm | Edge crushing |

| 32 | Bone tool frag. | Unit 3, 50-60 cm | Unidentifiable |

| 33 | Bone tool frag. | Unit 4, 10-20 cm | Unidentifiable |

| 34 | Bone tool frag. | Unit 4, 40-50 cm | Unidentifiable |

Other flaked stone artifacts recovered from CA-FRE-1333 include three modified flakes, a uniface fragment, two uniface retouch flakes, and a core platform rejuvenation flake. Rondeau and Rondeau (Appendix 2) suggest that the modified flakes and the uniface fragment may be associated with activities common to larger base camps and village sites. Finally, they feel that the range of formal lithic artifacts and debitage types is surprising for a collection this small. They find a unusually high formal artifact to debitage ratio and a high level of diversity for formal artifact types. However, this applies more to the midden deposit than to Rockshelter C, where the range of lithic artifacts and debitage types is more limited.

These artifacts, along with the lithic debitage and other topics, are discussed in more detail in Appendix 2.

Bone Tools and Production Waste

A single fragmentary bone awl (Cat. no. 6; Figure 9) was recovered from the M 1/3 of Unit 2. Also, three small unidentifiable bone tool fragments (Cat. nos. 32, 33, and 34; not illustrated) and three pieces of production waste (Unit 3, 40-50 and 60-70 cm, and Unit 4, 0-10 cm; not illustrated) were noted during the vertebrate remains analysis. These specimens are discussed in more detail in Appendix 1.

While by themselves not very diagnostic, the presence of these artifacts expands the range of activities practiced at the site. Bone tool production and modification are activities generally found in base camp or village settings rather than in temporary campsites or shelters.

It appears significant that all of the fragmentary bone tools and the production waste were from Units 3 and 4, in or downslope from the primary midden. Based on this, it likely that tool manufacturing or maintenance was practiced during Phase 1 of the Late Period as a part of the village or base camp's activities. The single bone awl from Rockshelter C was probably brought to the site and discarded after breaking. Bone tool production and modification were probably not among the activities practiced in the rockshelter during Late Period Phase 2.

Figure 9. Miscellaneous Artifacts from CA-FRE-1333. 13. Mano. 6. Bone awl fragment. 11. Core fragment. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

Figure 9. Miscellaneous Artifacts from CA-FRE-1333. 13. Mano. 6. Bone awl fragment. 11. Core fragment. Numbers represent catalogue numbers. Illustrations by Anna L. Runnings.

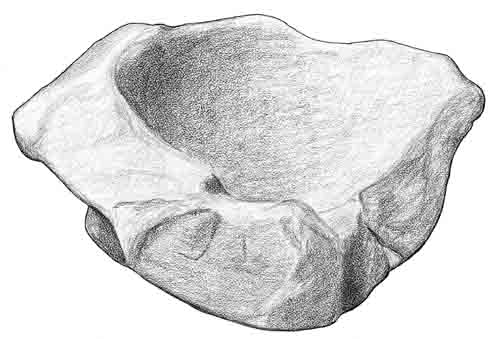

Ground Stone and Pecked Stone Artifacts

Only two artifacts from this category have been recovered from CA-FRE-1333. These are the granitic mano which was found on the surface below Rockshelter A (Cat. no. 13), and the sandstone bowl mortar recovered from TP1, above Burial 1, by Don Manuel and Bruce Crespin in 1980 (Cat. no. 19). A single bedrock mortar also is present in Rockshelter C. While the site record reports three bedrock mortars, two were determined to be of natural origin.

Figure 10. Bowl mortar (cat no. 19). Illustration by Anna L. Runnings.

The limited number of ground stone and pecked stone artifacts is unusual in a site thought to be a small village or base camp. It is possible that the lack of ground stone is due to the small sample size or that some of the ground stone artifacts have been collected by pothunters. However, battered and pecked stone artifacts usually are not considered important enough to be collected by pothunters, and no such items were noted during the investigations even though all rock was carefully examined. At present we have no explanation for this apparent discrepancy.

While ground stone is not very plentiful at CA-FRE-1333, two other sites in the White Creek area are known to contain extensive bedrock mortars. These are CA-FRE-1338, situated along White Creek some 450 meters to the northeast, and CA-FRE-1345, a small rockshelter on private property to the south. Each site has at least ten mortars; several at each site are 15 cm deep, and one at CA-FRE-1338 is 25 cm deep. (Site CA-FRE-1337, 200 meters north of CA-FRE-1333, was originally reported to consist of two bedrock mortars. Our examination, however, showed that both are of natural origin.)

Temporal Placement

It is our estimation that CA-FRE-1333 contains two separate components, although both date to the Late Period. The basis for this suggested temporal placement is discussed in the following sections.

Radiocarbon Dating

Four radiocarbon samples were submitted to the Radioisotopes Laboratory of the Department of Chemical Engineering at Washington State University for processing. All samples consisted of charcoal from selected levels or features from Units 2 and 3. The samples each weighed between 5.0 and 7.0 grams. The results of these samples appear in Table 5, below.

Table 5. Radiocarbon Determinations from CA-FRE-1333.

Radiocarbon age

Years B.P. | Laboratory No. | Provenience | Weight |

280 ± 60 | WSU-3555 | Unit 2 (hearth) | 7.0 g |

755 ± 50 | WSU-3556 | Unit 3, 40-45 cm (hearth) | 6.0 g |

1010 ± 70 | WSU-3557 | Unit 3, 60-70 cm (midden) | 5.0 g |

1420 ± 100 | WSU-3558 | Unit 3, 70-80 cm (midden) | 5.0 g |

The single date from Unit 2 (Rockshelter C) suggests that the use of the cave was during Phase 2 of the Late Period, or the Pacheco Complex as defined for the northern San Joaquin Valley (see Figure 11).

The three radiocarbon dates from Unit 3 place the primary midden within Phase 1 of the Late Period, or the Gonzaga Complex, although the length of that complex has had to be extended into what was thought to be a hiatus. The dates are internally consistent and support the impression that the deposit was undisturbed.

The lowermost sample from Unit 3, from 70-80 cm, represents the lowest level with sufficient charcoal in our soil sample for normal radiocarbon dating. Below this point the deposit becomes more and more sparse, suggesting that the date of 1420 B.P. probably extends to within a few hundred years of the initial occupation of the site.

Temporal Placement of the Shell and Stone Beads

Analysis of the shell beads produced age estimates which are in close agreement with the radiocarbon dates. A summary of the age estimates for the beads is presented in Table 6, and the full details are contained in Appendix 3.

Two of the shell three beads from Rockshelter C (Unit 2 and TP2) can be dated to approximately 450-150 B.P., within Phase 2 of the Late Period. A third shell bead, possibly dating 1000-1500 years earlier, does not appear to agree with any of the other age estimates for the site. Gibson feels that it may be a local variant actually contemporaneous with the other two beads from the rockshelter, and that the early age estimate cannot be supported.

The stone cylinder, although of unknown provenience, would fit comfortably with the age estimates for Rockshelter C.

The two Olivella beads from Unit 3 are of the same type, and appear to date between 950-450 B.P. This estimate agrees quite well with the radiocarbon dates for Unit 3, all of which are within Phase 1 of the Late Period.

Table 6. Age Estimates for Shell and Stone Beads.

| Cat. no. | Description | Provenience | Phase | Approx. Dates |

1 | Haliotis, epidermis disc | Unit 2, L 1/3 | L2-L3 | 450-150 B.P. |

2 | Olivella, Type G4 | Unit 2, R 1/3 | M2? | 2150-1850 B.P.? |

3 | Olivella, Type G2a | Unit 3, 20-30 cm | L1 | 950-450 B.P. |

5 | Olivella, Type G2a | Unit 3, 50-60 cm | L1 | 950-450 B.P. |

17 | Olivella, Type E1a | Test Pit 2, 20-40 cm | L2a | 450-300 B.P. |

18 | Stone cylinder | Unknown | L2? | 450-200 B.P.? |

Discussion

There is a very close agreement between the shell beads and the radiocarbon dates. Both place the primary midden around Unit 3 in Phase 1 of the Late Period, and Rockshelter C in Phase 2 of the Late Period. There was, however, no evidence of a protohistoric occupation.

This temporal placement agrees with the existing cultural sequence for the northern San Joaquin Valley. However, the Gonzaga Complex, originally thought to date from 1650-950 years B.P. (cf. Moratto 1984:192) should probably be extended several hundred years (Figure 11). In Unit 3 there was no apparent discontinuity or noticeable change between the lower midden (which provided a radiocarbon date of 1420 B.P.) and the upper midden (which provided a date of 755 B.P.). Furthermore, the uppermost radiocarbon date at 40-45 cm cannot represent the youngest part of the deposit. Burial 1, at that same level, clearly is intrusive, and also would date younger than 755 B.P. Finally, the two beads, which may originally have been associated with Burial 1, both suggest ages of less than 950 B.P.

There is no evidence of a long hiatus as has been proposed for the northern San Joaquin Valley. There are two (or three) radiocarbon dates and two shell beads from within the suggested hiatus between 1,400 and 600 years ago (Moratto, King, and Woolfenden 1978). The more limited hiatus from 950 to 450 years ago (Moratto 1984:193) also conflicts with one radiocarbon date and the two shell beads. However, this hiatus has been formulated based on evidence pertaining to the valley floor. The White Creek area, at an elevation of 2,400, feet may have provided a refuge during a time when the northern San Joaquin Valley was undergoing climatic changes which impacted the populations.

The evidence could, however, support a short hiatus at CA-FRE-1333. The function of the site clearly changed between Late Period Phase 1, when the midden around Unit 3 was deposited, and Late Period Phase 2, when Rockshelter C was occupied. Based on the dating evidence, there could have been a period of site abandonment between these two phases. There certainly was a drastic change in the function of the site (from a small village or base camp to an occasionally-used camp or shelter), and in the number of people using the site (from what may have been a moderately-sized family group to small numbers of travelers or hunters). There may have been a relationship between these changes and the hiatus proposed for the northern San Joaquin Valley.

Figure 11. Postulated Cultures.

There are some relationships between the cultural materials found at CA-FRE-1333 and those of the Gonzaga and Panoche Complexes of the northern San Joaquin Valley. The range of materials from CA-FRE-1333, however, is quite limited in comparison to the materials found during the water projects in western Fresno and Merced Counties. Also, many of the diagnostic elements for the proposed cultures are lacking entirely. Given the location and nature of CA-FRE-1333, a more limited range of materials would be expected. Also, the excavation sample is quite small--it is likely that a larger sample would produce a broader range of cultural materials.

The most notable discrepancy between the existing regional sequence and the materials present at CA-FRE-1333 is the lack of Panoche side-notched points, considered diagnostic of Phase L2. These points are reportedly common at CA-FRE-1345, some 900 meters to the south, and at CA-FRE-128 and CA-FRE-129. The lack of these points at CA-FRE-1333 is probably due to 1) the extremely limited nature of the cultural deposit, and 2) the function of the rockshelter during Phase 2 of the Late Period.

CONCLUSIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS

Based upon our investigations, it is our opinion that site CA-FRE-1333 is a significant cultural resource (this is discussed in more detail in the following section). It contains intact and undisturbed evidence documenting the occupation of the White Creek area during prehistoric times, particularly during Phase 1 of the Late Period. Activities which we believe took place at the site included village or base camp activities during Phase 1 to sporadic camping or hunting activities during Phase 2 of the Late Period.

Our interpretation that primary midden at CA-FRE-1333 corresponds to a village or base camp is based on several lines of evidence. First, it appears that the site was occupied by one or more families for an extended time, and that both subsistence and non-subsistence activities were carried out. In the primary midden there is evidence for the following:

- Food procurement (activities probably included gathering, fishing, hunting, and trapping)

- Food preparation (including acorn and seed grinding, butchering, cooking, etc.)

- Interment (two burials were found in one unit, suggesting that at least several more should be present in the deposit)

- Manufacture and maintenance of bone tools and a variety of flaked stone tools, and

- Return to and use of the site over an extended period of time (nearly 1,000 years), suggesting a continuity of tradition on the part of a group rather than isolated activities by individuals.

Based on these points it is likely that a small group, perhaps an extended family group, inhabited this site periodically as part of a seasonal round involving a significant area. The activities practiced were more than would be expected at a procurement station or a temporary campsite--visits probably were measured in terms of weeks rather than days. It is apparent that hunting, gathering, and some fishing trips were made from the site, and that food and other raw materials were returned to the site for processing, possibly storage, and consumption. While occupying the site the inhabitants buried their dead, rather than returning them to a village at some other location for ceremonies and interment. This site, while not large, was considered home to its inhabitants.